|

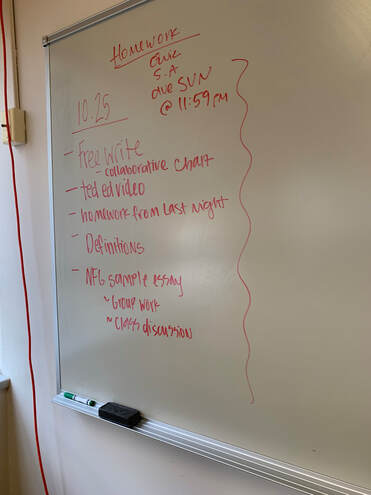

With only three weeks left in the semester, I think we feel the pressure and stress this time of year brings. For my first-semester first-year students, this is their first time preparing for college finals. This semester has been full of unique and additional challenges, and many of them are looking forward to the semester ending, Christmas break, and going home to their families. For their final in this class, they’ll be turning in a portfolio reflective of their work this semester alongside a 3–4-page reflection essay. Thanksgiving is next week, and when we come back from Thanksgiving break, we have dead week and finals week before the end of term. That frantic energy of holiday excitement combined with the particular anxiety this semester has brought has combined to form an unease that my students can feel in the classroom. Navigating that unease has been part of my responsibilities as a learner-centered teacher. I’ve been flexible this semester, willing to pivot to students' needs, and attentive to the various challenges these students face. Our third unit has had us reading and considering technology, social media, loneliness, and surveillance. Wrapping up the third unit and preparing for the accompanying paper, an argumentative essay, we’ve spent time watching a movie, reflecting on our feelings about the subject, collaboratively forming our rubric, and doing group activities to finish the list of readings. One of the productive activities we did last week was to divide the class into a few groups and assign one article to each group. They had time to read the article independently, then to meet with their group and discuss it. Next, they had to answer specific questions and have a notetaker write their answers and then nominate someone as a spokesperson. Each group presented the critical information of their source to the class, so they were teaching each other. I took notes as they spoke and then shared the document with everyone at the end. Next time, the only thing I may do is nominate someone else to be a note-taker or a note gatherer instead of me. Ultimately, this activity kept students engaged, employed group work, and had students teaching each other. This enacted peer-assisted learning, discussion-based learning, collaborative learning, and invoked Vygotsky’s zones of proximal development. I started reading the second edition of Weimer’s Learner-Centered Teaching, which I highly recommend. One of the things about learner-centered teaching is that it requires critical reflection and that our role shifts to facilitation of the acquisition of knowledge. Our teaching isn’t dependent on what our students know when they enter our classroom but on what they can do. In learner-centered pedagogy, the student becomes a true partner in their learning journey. As I look back over the 14 weeks of this semester, I wonder how successfully I’ve achieved my goals as a learner-centered teacher. I can see ways I’ve succeeded—incorporating voting for decisions and topics, having the students make paper 3’s rubric, incorporating discussion, and frequently engaging group activities. I can also see many ways to improve, especially in course content, instructional design skills, and relying too much on extrinsic motivation to power learning. I’m excited about reimaging my course for this Spring when I’ll be teaching ENG 101 again, and I have a lot of ideas about how to continue to shift the power balance away from teacher-as-

0 Comments

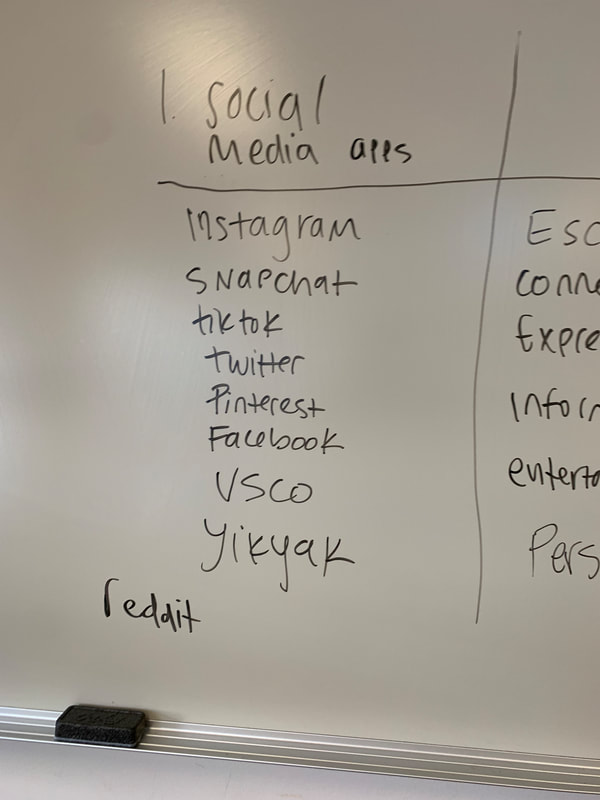

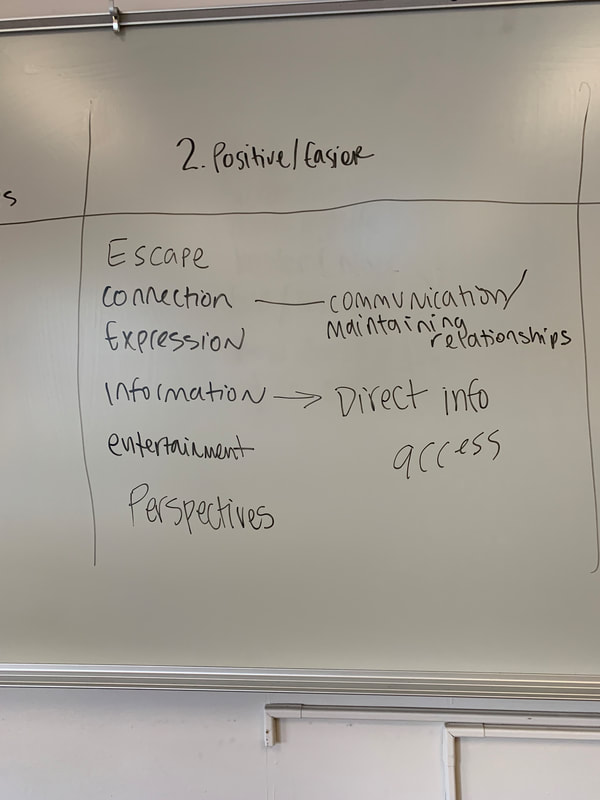

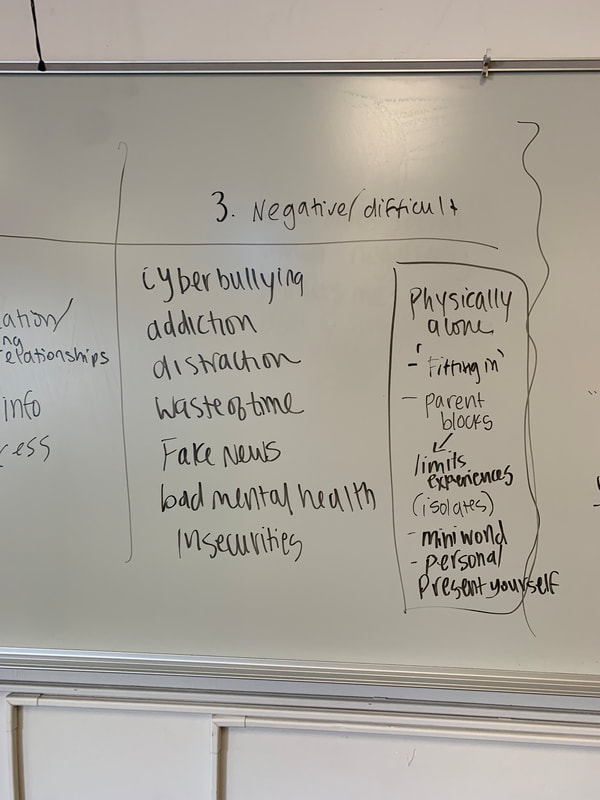

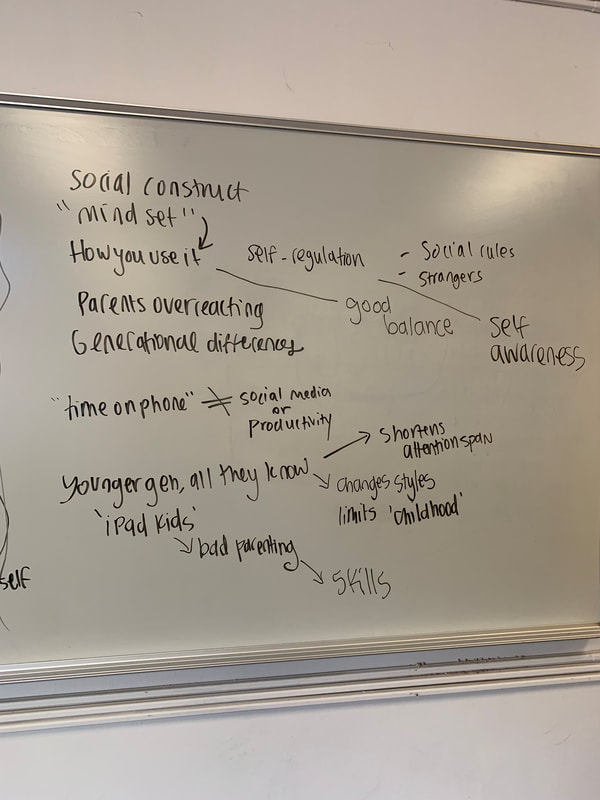

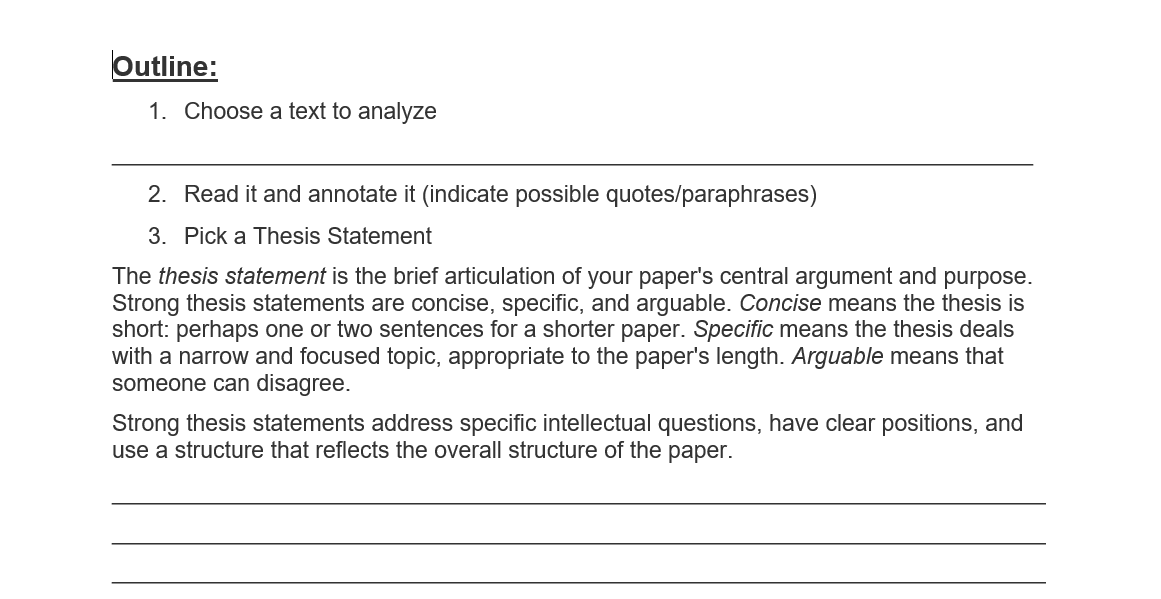

The last couple of weeks have been a unique challenge because students, especially first-year students, are facing more difficulty this semester than seemingly any semester prior. The ongoing pandemic may no longer be ushering us into virtual classrooms, but it continues to impact us in unforeseen ways. Students are exhausted, struggling, having a more challenging time focusing, and operating at lower energy levels than I’ve ever seen first-year students operate. I’m sure, years from now, someone will be able to label exactly what we’re experiencing, maybe they’ll even assign it a particular name or condition, but for those of us living it–we’re just making it day by day. I am remarkably proud of the work that these first-year composition students are producing, despite the challenges. We have made it through two out of three of our major units: visual analysis and textual analysis. We are in the midst of our final unit: a position paper; some would call this an ‘argumentative essay.’ We’ve been reading a variety of articles about social media, technology, and surveillance. These articles will eventually provide their sources for this upcoming major paper. We’ve had various discussions about the impact of social media on our lives: good and bad. We’ve hypothetically considered what life would be like without social media if it were to be banned. We’ve talked about app tracking and read about the quantity of time we spend on our phones and how that may be altering our brain chemistry. I’ve noticed that the most participation in one class session I’ve ever seen this semester was on the day we talked about social media. The semester is rapidly slipping away from us. It’s already the first week of November, and we have about one month left of Fall 2021, and Thanksgiving break is sandwiched in there. We’ll wrap up unit 3, they’ll turn in their third final paper, and we will work on revision in preparation for their final portfolio. I feel like the most important thing for me, at this point, is to continue caring about my students as people. I think that prioritizing empathy and kindness has to be first if we want to empower students to build lasting foundations in their academic journeys. With these additional difficulties, many of which are the result of COVID-19, I think this first year of college will determine whether students decide to continue on. I think of my role as helping them value critical thinking, believe they can succeed, learn time management skills, as well as demystify academia for them. If I can do that, the hope is that they have a strong enough foundation to push through, even when things feel hard—more complex than ‘normal.’ I fear we’ve lost what ‘normal’ was, and we may never get it back. It’s such a shame if that’s the case because I love teaching and learning, and I want students to enjoy learning. Suppose the university feels extraordinarily difficult with the pressures pushing in from external situations. In that case, we have to pivot inside the space we have—otherwise, we won’t be teaching well, and our students won’t be learning. I don’t have complicated solutions for doing this beyond ‘teaching against the grain,’ prioritizing empathy, eradicating busy work, thoughtfully building syllabi, purposefully assigning homework, and assessing in various ways. This week, I started reading Mike Rose’s Lives on the Boundary. I’m only a few chapters in but what I see through Rose’s autobiographical narrative and his reflections on our education system is that our systems have failed us. It isn’t that education isn’t a wonderful, powerful thing. It’s that the design of education is failing both students and teachers. We’re bending to the demands of neoliberalism, test scores, or nationalist ideologies rather than tailoring the educational system to the needs of learners. Much like the legacy of our nation and the manifest destiny imperial arm that casts a shadow over the America of possibilities, our education system is built to punish. It operates in a carceral fashion. Mike Rose thought of education as an invitation, and in so doing, he humanized his students in a way the system can’t. Instead of labeling students according to their failures, he saw a world that could be, and his compassion is evident in the lines of his 1989 book.  Works Cited Rose, Mike. Lives on the Boundary : a Moving Account of the Struggles and Achievements of America's Educationally Underprepared. New York, N.Y., U.S.A. :Penguin Books, 2005. We’re approaching the middle of the semester, and mid-term grades were due today. The past two weeks have encompassed our second unit in Composition 101—textual analysis. Their final draft is due next week. During week 6, we focused on learning about paper organization, using quotations from sources, transitioning in an essay, and annotation. One day, we discussed both Malcolm X’s speech Ballot or the Bullet and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail. Examining these two texts side-by-side was beneficial because they both directly address their audience specifically in their text and exist at the same historical moment. Both historic civil rights leaders were assassinated following these speeches/letters. It also provides two different forms—letter vs. speech. In addition, both leaders rely heavily on pathos but in remarkably different ways. I found this was a productive and thoughtful combination of readings for this course. Later in the week, we reviewed the difference between summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting sources. We also did an in-class annotation activity. I printed a two-page worksheet that included an excerpt of a text and instructions/questions for annotating. I provided each student with a new highlighter that I told them to keep and use for future annotation or their upcoming project. They spent time reading, highlighting, annotating, and answering the questions in class. Then, we discussed their answers. I used an excerpt from the short story “Desiree’s Baby” by Kate Chopin. This was a fascinating story to include because the story has many French words. It was set in slavery-era Louisiana, and it discusses race and racism indirectly through the narrative. It also has a dramatic ending. The discussion about “Desiree’s Baby” also made room to review some of the last things we discussed, such as social constructs, Jim Crow, Plessy V. Ferguson, and the ‘one-drop rule.’ This past week, week 7, our course objectives included organizing, planning, and drafting textual analysis. On Monday, we reviewed grammar for communication. A colleague of mine put together a short PowerPoint engaging some of the most common grammar errors we noticed after project 1. We walked through a sample textual analysis from our course textbook, Norton Field Guide USM Edition, and discussed each paragraph. On Wednesday, I brought in an outlining worksheet for them to complete in class. We reviewed the entire project two rubric and marked up a sample thesis together to give them an example while they worked on their outline worksheets. They had to pick the text they wanted to analyze during class time—if they hadn’t already. I walked around as they completed the worksheet, which asked them to pick quotes, write a thesis, and choose critical points from the thesis to use as body paragraph points. I gave them 30 minutes to work on this independently and then walked around to each person. I asked each student what text they chose and their key points and asked how they felt about their thesis. Every student left the class that day with at least their thesis written and knowledge of their key points. I felt like this was successful as it broke down the paper writing process into more manageable pieces. This upcoming week includes a peer review workshop and a class dedicated to revision strategies. At the end of next week, their textual analysis is due. Over the last four weeks, we’ve committed in-depth time and activities to thesis composition, paper organization, annotation, citing sources, summary and quoting, and writing thoughtful paragraphs with lead in sentences and topic sentences. The hope is that each student has gained the knowledge of composing a textual analysis and general paper writing skills that will benefit them throughout their college career. Sometimes, it does feel overwhelming to bring in texts that can be controversial or talk about social constructs such as racism or sexism in the classroom. I think it’s easy for some folks to argue that composition is a classroom space that should be apolitical. However, I don’t think that’s a strong argument because of composition theory’s overlap with cultural studies and the acknowledgement of pop culture and the world around us. Composition is what we teach and learn, but our learning is often real people’s experiences, contemporary events, individual narratives, etc. Much like critical pedagogies, cultural studies folded into composition theory and considered the importance of enabling students to understand power distribution (Tate 97). Composition studies is necessary to students’ formative education. It has a subject matter and object of inquiry; that content is our realities, cultures, and lives. The content in comp as realities/culturally relevant texts is a marker of the public turn; composition studies are connected to real-life experiences and understanding them. Students should be encouraged to analyze the world around them and how media functions to become participant observers and understand themselves as consumers and producers of culture. Our composition studies naturally fixate on investigations beyond the classroom (Tate 105) and to our local terrain and the world beyond. I think it’s intuitive to continue bringing in socially relevant readings, especially since we’re teaching students how to critically think, determine their opinions, and use textual or visual evidence to support their claims. These are just good life skills that are helpful in and out of the classroom. Now that we are five weeks into the semester, we've settled into a routine. We had a rocky start to the semester with the unknowing that a rise in COVID-19 cases brought, lack of clarity from the administrative regarding our campus plan, and the impact of Hurricane Ida. Having two weeks free from those additional external complications helped a lot in terms of setting expectations and building a classroom space that is welcoming and inclusive. I'm getting to know my students, who are all fantastic and attentive, and I've enjoyed learning their names and embracing a classroom flow. In the past two weeks, they've turned in their first major project: a visual analysis. I have graded their projects and returned them with feedback. Clear feedback from teachers on student work is important to their progress and confidence (especially in first year writing courses) but, as a teacher, this process can feel daunting at times. Before I began writing feedback on student's submissions, I organized a set of pre-written comments in three levels (well done, decent attempt, needs considerable improvement) in a word document for each major component of their assignment. When I went to comment on their work, I began by addressing the student by name and adding a personalized sentence or two to each one in addition to the pre-written comment I copy and pasted in, but these pre-set comments on the necessary pieces of the project made the task feel significantly less overwhelming. I was still able to tailor my feedback student-by-student, but this process ensured that they knew why they were getting the grade they received and how to improve moving forward. It also standardized both my grading and responses. I've already received a few comments back from my students on their grades/feedback including one student who wrote, "I’m so thankful that you give such great comments. You are the only professor I have that communicates efficiently with their students." This response made me feel secure in my feedback process, although I used a list of pre-set comments to help outline each student response, it didn't alter their experience or decrease the usefulness of those comments. This past week, we've transitioned to discussing textual analysis. I noticed in our previous conversations that many students were not well acquainted with how to write a thesis nor how to summarize text. On Monday, we focused on summarizing text. During class, I prepared a PowerPoint with key points from the textbook followed by an in-class summary group activity. I provided each group with a few paragraphs about textual analysis, argumentative essays, summarizing etc. all from Purdue OWL's website, and each group had to summarize their section and then nominate one spokesperson to teach the class their part. This exercise engaged peer-assisted learning, summarizing skills, and peer-teaching. On Wednesday, I began class by writing our objectives for the class session on the board, as we always do. I also arrive a few minutes early to set up all the technology components and during that time, I typically play music through the computer speakers. Last week, I put a discussion board on the course canvas asking for music recommendations and I was pleased to see two people suggested bands/albums, so I picked one and played that while students funneled into class. We began the day by walking through the expectations of their next major assignment, a textual analysis. Then, I went through a short (~8 minutes) PowerPoint about crafting a thesis with examples. After that, they did an in-class independent activity where they had to pick a song and find the thesis of the song and write out a few bullet points of evidence for their thesis. My example was Jolene by Dolly Parton and I shared my thesis and ‘evidence’ which I had compiled the night before. They were extremely invested in this activity and wrote for almost fifteen minutes before I asked to hear a few volunteers share their thesis. I collected these at the end of class and made a Spotify playlist of their songs which I shared on the Canvas. https://open.spotify.com/playlist/6qOlW4WFGePW4AjbePEDbe?si=6da283f3b9134250 After our thesis activity, we shifted gears to talking about language and identity. I had them flip over the piece of paper they’d done their prior activity on and respond to two questions in complete sentences:

The next thing we did is that I wrote out the states they were from on the white board. I asked for them to tell me what people said about their state. In our class, everyone was from Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, or Texas. I do have one student from Florida, but she was sick that day. I wrote their responses about what people said about their states and commiserated with the Louisianians about how people have asked us if we have a pet alligator or took a boat to school. We took a moment to reflect on what people thought about us versus the truth. We also discussed how our ‘language,’ or how we sound often determines how people might respond to us. At this point, we had about 25 minutes of class remaining. I had them take a little less than 15 minutes to read Amy Tan’s Mother Tongue quietly to themselves, although it was assigned for homework. I told those who already read it to take notes and prepare something to say in response while others read it for the first time. While they read, I drew a picture on the board showing the interconnectedness between identity, language, culture, social constructs, and systems of power/privilege. I also wrote the definition of social constructionism, a sociological theory, on the board. When the timer went off, I quickly explained the picture I had drawn on the board and went through the definition alongside a quick explanation of why theories are useful to us in conversations and analysis. Then, I had students raise their hands and share what they thought about the essay we read. After each student commented, I related their comment to the picture on the board regarding the connections between language, identity, culture, power, and social constructs. As the clock told me I only had a minute or two left of class, I thanked them for their answers and reminded them of the homework and my office hours and they left for the day, depositing their papers on the desk as they left. Looking back on these weeks, we packed a lot of content into our class sessions, and I know we will continue to do so. I’m really proud of my students, who are predominantly freshmen, for being adaptable and trying hard despite the external circumstances of attending high school and now college in a global pandemic. I am excited to start talking about close reading next week and to dive into more course readings.  The last two weeks have felt overwhelming and challenging, with Hurricane Ida making landfall the weekend before Week 2 of our sixteen week semester. The University of Southern Mississippi canceled classes on the first Monday of Week 2 because they weren’t sure what weather Hattiesburg would get because of the Category 4 hurricane approaching. School started back on Tuesday after the storm turned east, and Hattiesburg received little destruction as a result. However, many of USM’s faculty, staff, and students are from Louisiana like I am. From our icebreaker activity on day one, I knew that a little over one-third of my classroom was from a city in Louisiana that was navigating the impacts of terrible flooding and extreme wind damage. That week, the class was already scheduled as an asynchronous course. Ahead of the hurricane, I prepared an overview video explaining how to navigate module week two on Canvas, find the instructional videos and complete assignments. I scanned the textbook pages assigned reading because the school bookstore had not yet received copies of the books. I also sent an announcement via Canvas reminding students about the week ahead, and I included hurricane tips for those who had yet to live through a hurricane. It ended up being a good move on my end to have completed these tasks before the hurricane made landfall because the aftermath impacted my family, and I wouldn’t have been available in the same capacity early in the week. I hosted my office hours this week on Zoom. Going into week 3, I received news from the University that we would be in person for the duration of this semester. Previously, we were waiting to confirm this was the case as COVID-19 cases increased across the state. Knowing that I would be teaching synchronously in person, I prepared my lesson plan accordingly. With Labor Day taking one of two class days away from my time with these students, I prepared for Wednesday’s class to be complete and involved. Ahead of Wednesday’s class, I printed off handouts outlining the peer review expectations with guiding questions. I also made name cards for each student and brought loose-leaf paper for our in-class writing activity. Arriving at class a few minutes early, I prepared the technology I would use and played an album on YouTube as students came in. I also wrote the class objectives on the board:

At precisely 1 pm, I began class by handing out their name cards. As I called names and passed out the papers where I had folded them into three parts and written their names in sharpie, I explained how I would take attendance in this class. I prepared these name cards to get to know students names and so both their peers and myself could see their names if we wanted to reference something they said in the discussion. Also, that’s how I would know who came to class based on whose name cards were given out and whose were not. At the end of each class, I expected them to return their name card to the bin by the door. Next, I reminded them of their upcoming rough draft due for their first major visual analysis assignment. I explained the importance of peer review and told them that we could do our peer review one of two ways. Option A was to read each other’s drafts over the weekend, answer the questions in complete sentences, and draft their answers as a letter to their peers. Option B was that they could reach each other’s drafts over the weekend, answer the questions briefly in bullet points, and then on Monday in class, we would split up into their small groups to give more comprehensive verbal feedback. They would use their bullet point notes as a jumping-off point to remind them of their comments for the class peer review. I explained why voting in the classroom was a good idea and why I liked to involve their opinions. 20/21 students voted for Option B. I shared a PowerPoint with them that I had already uploaded to their canvas Module that morning. I began the day’s presentation with a review of what we had learned the week before when we had been asynchronously learning. For this review, I used the student’s quotes from their discussion post #1 and discussion post #2 to define the fundamental concepts of our unit. Although the students did not want to read their comments, I could tell it was a surprise to see a teacher involve their work in the class learning. To bring these concepts together, I showed them a Cajun meme and together, we applied our key concepts to the image, a Cajun meme, which is a particular thing with needed context and a niche audience. My lecture, purposefully called a mini-lecture because it was intentionally short, continued by highlighting the unit's key points, including context, the importance of a good thesis, how to write one, and a few additional details regarding composing a visual analysis. I paused for questions, but students did not have any. I followed the presentation with a short in-class writing assignment that I collected. Our last activity for the day was reading an example of visual rhetorical analysis and talking about it. I set a timer for 12 minutes and played study music in the background while reading the example independently on their phones or computers. While they read, I wrote a chart on the whiteboard with two columns. After the timer, I asked students to pair up with their desk buddy (each desk has two seats) and talk about one thing they thought was excellent about the example, and one thing they thought could’ve been improved. After a few minutes, I asked them to call out their answers. Together, we filled in the columns on the board. Looking at our remarks from the example, I explained what they may want to look out for as they write their visual analysis. With only a few minutes left in the class, I reminded them of the upcoming deadlines and my office hours. As they left, they deposited their name cards where I asked, and many wished me a good day or told me goodbye. Looking back on the class, I thought that we packed a lot into the hour and fifteen minutes and that the students were good participants. I felt like the classroom's energy was good and that teaching in-person probably has something to do with that excitable energy. The students were well behaved if a little rigid. One of my objectives is to see them loosen up during the semester and be more at ease in the learning environment. Preparing for next week, I did feel as though my transitions between tasks were a little choppy and less seamless as they could’ve been. As I draft my lesson plan for my upcoming classes, I want to consider how to transition from one item to another. I know that we are our own worst critics, and it’s even possible that the students didn’t notice my less-than-seamless transitions. However, it is something I can work on, and therefore I will. This past week in my Comp/Rhet Theory class we discussed teacher response at length. As their first major assignment deadline approaches, I’ve been thinking more critically about my feedback on their short assignments. Thinking about giving more facilitative feedback than directive helps make my ideas about student response more concrete. Although I think a good rule of thumb is to extend kindness and aim to support students in their educational journeys – not tear them down – and that’s something I never had to be taught to do. There are more intentional ways to give helpful feedback beyond just extending empathy (necessary but not complete). The following is a written summary with key points included of the work referenced above and cited below.  Beth L. Hewett is owner and president of Defend and Publish. She manages the coaching team and is the company’s Executive Coach. Beth holds a PhD from The Catholic University of America and an MA from Kansas State University. A postsecondary educator since 1980, she has taught basic to advanced writers, including multilingual and learning-disabled writers. Beth’s research interests are in online literacy instruction in digital settings, nineteenth-century American rhetoric, and grief education. In Hewett's chapter about online and hybrid writing instruction, they begin by engaging a historical view of literacy education. Beginning in Greece and Rome, they outline rhetoric passed orally from teacher to student and the teaching processes of philosophers like Socrates. Others like Aristotle and Cicero used written mediums alongside oral instruction for communication and teaching. As writing tools developed and technology changed, so did the frequency of written communication. With the invention of the printing press, America in the 19th century saw oral speech meeting written knowledge and curriculum shifting. As textbooks became more accessible, the American rising middle class acquired literary skills. Throughout the 20th century, correspondence teaching used writing technologies for distance learning. In the late 20th century, microcomputers emerged. Following this, computers became more accessible and technology improved in such a way it was able to be used across social classes. Out of this, OWI extended distance writing education. People held various views about OWI being affective for learning. Computer technology was predicted to change how writing was taught. Some scholars were optimistic about the future of distance learning. There is a divide between those who are adept at using technology and those who are not and their opinions about OWI differ. OWI is not one specific way of teaching; instead it is composed of building blocks. Those building blocks are course setting, pedagogical purpose, digital modality, medium, and student audience. Setting? Fully online classes are those with no face-to-face components. Hybrid classes meet in either distance-based or computer-mediated settings AND in tradition in-person classrooms. These are sometimes called mixed mode. OWI's pedagogical purpose is simply to teach and learn writing. Pedagogical purpose should account for both feedback and interactivity processes. To achieve these pedagogical purposes, institutions should provide writing support, technology support, and fewer students per course. Ideally, students would have access to an online writing lab on campus. Modality shapes interactions among teachers and students and modalities are reliable as specific tech/software come and go. Some folks believe that asynchronous courses are less personal than synchronous ones. Asynchronous teachers must engage their students with intention and thought. Synchronous modalities provides immediate response and communication. The medium in which these classes are taught differs from modality. Most teaching and learning occurs textually making text the most common medium. Voice/audio is often missed in text-based courses. Video is used at times in distance learning. There are plenty of options for voice, audio and video platforming as well as collaborative whiteboards and synchronous meeting spaces. When settings modalities and medium are selected intentionally, powerful teaching and learning can happen. Oftentimes, OWI students are first year writing students in higher education. This presents additional challenges as these students are not yet experienced in navigating college courses. Studies suggest that students need preparation to succeed in online writing courses. Difficulties or challenges in online writing courses can be exacerbated for marginalized students. Technology availability is not one of the five components/building blocks of OWI. However, availability is necessary for online learning to occur. Many times the technology needed to succeed is provided by the university. This is something to consider. There is still much we don't know about student populations that are multilingual, non-traditional, etc. More research would be required to adapt components that would benefit these learners. Technologies for writing will continue developing over time.

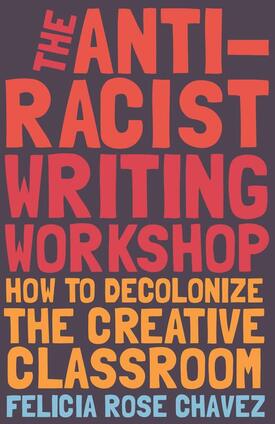

You can explore Felicia Rose Chavez's various consulting opportunities on their website -www.antiracistworkshop.com/consulting-services What people have said about the book: “There is power in the words we write. Understanding how we can use those words to build community, challenge racism, and decolonize classrooms is the work of anti-racist educators. Felicia Rose Chavez has skillfully and lovingly done all three in a book that will transform how we write to create an anti-racist world. The writing rituals, questions to push anti-racist thinking, and explanation on how we complete the literary canon will leave the reader with the necessary tools to become a teacher who is building a new world. Chavez lays out powerful and inclusive ways to model a writing workshop structure that would make June Jordan proud.” —Dr. Bettina L. Love, author of We Want to Do More Than Survive Chavez writes in the preface, "Here is my own testament, my own movement, a blueprint for a twenty-first-century writing workshop that concedes the humanity of people of color so that we may raise our voices in vote for love over hate" (xii). In the introduction, Chavez remembers her time at the University of Iowa in their Nonfiction Writing Workshop. While many considered Iowa City a quaint, walkable, paradise, Chavez had a different experience navigating the city as a Chicana writer, often assumed to be an employee at the places they went as a patron. As a person of color, the pressure to feel unable to complain was compounded by the assertion that she was just 'lucky to be there.' "Silencing writers," Chavez remarks, "is central to the traditional writing workshop model." For those unfamiliar with the traditional writing workshop, this model commands that participants read a classmate's work ahead of workshop and mark it up. They will also write a critical response in letter form addressed to the writer. When everyone meets up in a class called "workshop," everyone will share their opinions and thoughts while the writer of the work being discussed takes diligent notes and sits in complete silence. In 1936 when this model was created, the students in these spaces were homogenous: white men of a particular class. Today, however, our demographics look very different from an institution of higher education in 1936. Only 55.2% of college students are white or Caucasian and the rate of female college attendance has increased 34.7 since 1960 (College Enrollment, 2021). This book Chavez has written is about institutions and institutional racism. Institutions of dominance and control reproduced in the traditional writing workshop and upheld by primarily white workshop leaders and majority white workshop participants in addition to canonical white authors as required texts. Chavez writes, "The anti-racist workshop is a study in love. It advance humility and empathy over control and domination, freeing educators to:

The anti-racist model emphasizes the author's lived experiences and their expertise in their own writing. The author is encouraged to moderate their own workshop, views contextualization as important and shifts the workshop leader from an authoritarian control-wielder to an ally, facilitator, collaborator, and encourager. In the book itself, Chavez provides a blueprint that navigates fundamentals of both protecting and platforming writers of color. This pedagogy "imparts a pedagogy of deep listening" (p. 17). Citations:

“College Enrollment & Student Demographic Statistics.” EducationData, 7 Aug. 2021, educationdata.org/college-enrollment-statistics. The following is a written summary with key points included of the work referenced above and cited below. Scott Warnock is a Professor of English and Director of the University Writing Program at Drexel University. Warnock teaches first-year writing and courses such as Writing in Cyberspace, The Literature of Business, Language Puzzles and Word Games: Issues in Modern Grammar, and The Peer Reader in Context. In 2020, Warnock was awarded Drexel’s Christian R. and Mary F. Lindback Foundation Award for Distinguished Teaching.

In "Teaching the OWI Course," Warnock opens his chapter with a question that applies to any pedagogy-specific principles, How do instructors teach writing online well? Guided by that question, Warnock's chapter considers five OWI principles focused on pedagogy in online instruction including teacher presence, strategies for building and encouraging conversation, responding to student writing, class management, class organization, course evaluation, assessment and technologies. Teachers should aim to be true to themselves and sometimes, teaching in a mode they're unfamiliar with can challenge their ability to be authentically themselves and comfortably enacting their teaching philosophies.

Instead of getting caught up by the technology itself or getting stuck as the IT consultant for first-year students, OWI needs to focus on writing above all else. How do you build an online class that feels like a writing class instead of allowing students to get caught up by the environment? First-year instructors are often at the front line of new students interactions with syllabus, campus, technology, etc. To prevent first year writing instructors from transforming into IT specialists, they require multi-level support from their institution. The institution should provide clear, easy to access help through their IT department and communicative help desks. Thinking about mediating technology concerns, online writing instructors should also have alternate lesson plans in place if technology they wanted to use fails and can't be fixed. In order to decide whether they want to use a new digital technology or not, David Jonassen suggests using a risk-benefit-type analysis structure. This risk assessment essentially asks of us: does the benefit of using this new tech outweigh the risk it won't work? That said, teachers should get in the habit of having back up plans. In general, planning well helps to maintain course focus and not get distracted by other issues that may arise. If a teacher has adequate time to plan their course, build their structure, and troubleshoot new technology: they will do better teaching an online course than if they receive pressure to get things done quickly. Overall, teachers should strive to maintain an environment that is inclusive for all. Planning while being mindful of accessibility concerns and mediating those concerns before the class begins is ideal for online teaching and learning.

OWI courses are writing courses. That said, teaching writing digitally can open up opportunities if teachers control the technology instead of allowing the technology to control them. Teachers should be able to adapt and move between online and face-to-face teaching well and simultaneously maintain their teaching philosophies. Warnock suggests we look closely at our "teaching selves." Teachers must also think about digital technologies comprehensively before using them in the classroom which returns to how teachers conceptualize themselves. Teachers should consider 1) what they want to accomplish 2) how technology complements those goals and 3) they should reflect frequently. Online teaching requires excellent communication. Because so much of online learning requires text communication (emails, announcements, assignments, feedback, etc), teachers must be extremely specific with language, undeniably clear, straightforward, and concise. Teachers must also proofread intentionally, revise for clarity, and appropriately repeat instructions. In addition, OWC's need ground rules: rules for how we communication with each other, rules for discussion, etc. In order for students to succeed in asynchronous online courses, teacher's presence needs to be felt. As the reading and writing load increases, so should the need for clarity and teacher modeling. Many OWI's are text-centric; teachers should consider how much time their students are spending and how much time they must spend to provide appropriate feedback in return. Using audio/video technology can enhance the online classroom experience. "Thinking digitally" should mean finding ways to widen communication opportunities and being open about what that could look like. Introducing multi-media content can be one way to achieve this. That said, it is also important teachers consider accessibility issues that come with multi-media content (image descriptions, captions or transcripts for audio, etc.) Teaching online may require teachers to consider their responses to student writing differently. Giving feedback on student writing is incredibly important to student's learning. As teachers craft these responses, we should also consider our purpose, audience, and context when we write to students and be incredibly direct. "As Hewett (2015a) indicated, such a problem-centered approach could include asking open-ended questions; demonstrating; illustrating; and, again, modeling (specifically modeling at the level 'being required of the student'). Teachers cannot assume that the ambiguity inherent in open-ended questions is appropriate for all learners....Teachers need to think about the clarity of writing vocabulary and other instructional terms" (Hewett, 2011, p.12). Moderation is important to online learning environments. Facilitating space for discussion peer-to-peer is beneficial for various reasons, however, teachers need to moderate conversations that occur in the digital space. This can be a challenge. Online discussions are not linear in the same way that in-person class discussions often are. The online space may also remove some shyness from students. As a teacher moderates the less formal online discussions, they should consider any accessibility issues, define ground rules ahead of time, and challenge students to ask critical questions and prod beyond what's on the surface. Low-stakes writing assignments are important for self-reflection, collaborative proofing, engaging students in process, and preparing students better for major assignments. It is important that teachers respond to student work. It is also time-sensitive.

Teachers should ask themselves what they do best and what they value most. Then, they should do those things in the online space. This is what Warnock describes as the "migration of pedagogy." In other words, we're not reinventing the wheel. We should be using technology to thoughtfully build assignments, to organize the course clearly, and to facilitate dialogue that will go beyond the four walls of the classroom or in this case, digital walls.

Teaching may not be ours to control fully. It is not recommended practice to use someone else's course materials. It is not effective to copy and paste someone else's content. We must personalize our courses, even if we do use elements that are borrowed. Personalization is incredibly important to good pedagogy. That said, a template may be incredible helpful. Using templates or core's can be productive for building out course content and making it easy to navigate for students. Good teaching requires great communication and flexibility. Teaching must be wiling to adapt in order to provide quality classes. Teachers should be prepared to provide accommodations. Considering this, institutions should also be providing support for their instructors. "A culture of reasonable control and flexibility gives an OWI program the best chance of doing what it is there to do: teach students to write more effectively" (Warnock, 2015, p. 174).

Teachers should be willing to motivate students to learn, not only transmit knowledge into their heads. These courses and structures used in OWI should be highly personalized, thoughtfully built, and created by writing instructors, not administrators. The classes must be consistent with the teachers pedagogy of philosophy as well as the program they are in. One weak point in WPA/OWI and other writing programs is the assessment and evaluation of online writing instructors. We need more for assessment of online instructors as the current evaluations are often extremely critical, ineffective or measuring the wrong things. Assessment would help courses adapt and improve. Unfortunately, useful teacher evaluation is a pedagogy problem not exclusive to online teaching. Summary: This chapter written by Scott Warnock focused on the principles of OWI. There is no one way to be successful. Experimental teaching provides new paths forward and accessible, inclusive paths forward. OWI practice is exciting and takes advantage of digital tools. Online writing instructors should still primarily be writing instructors, should maintain their teaching practices and philosophies, be extremely flexible, be supported by their institutions in their flexibility and teachers cannot abandon effective practices for a technology: OWCs maintain core effective teaching practices. Blogger's Note:I wanted to call attention to some strange uses of language in Warnock’s chapter that felt like co-opting. In the chapter, there was more than one instance where Warnock or a quoted person utilized language/phrasing that is taken from marginalized people in very different situations and applied to less vulnerable populations in an academic situation. One prominent example of this is on page 167 in the section under OWI Principle 4, as Warnock discusses the “migration of pedagogy.” He quotes a senior faculty member who “expressed that he felt colonized by teaching technologies.” Warnock goes on to add, “I think it is important not just for teachers but also for those involved with faculty development and instructional design to understand this thread of colonization.” Our world is still actively feeling the impacts of colonization, and although we study post-colonialism, we aren’t really beyond colonialism in our world. Globalization, imperialism, forced assimilation, and even modern Christian missionaries still enact colonial principles and oppress marginalized folks in active ways both here in the U.S. and abroad. It doesn’t feel appropriate to equate the violence and oppression of various peoples to a teacher feeling overwhelmed by new technology. Another example is when Warnock quotes Susan Lowers (2008) on page 156, “Much like immigrants who leave the cultural comfort of their home societies and move to places with very different cultures and social practices, those who teach online leave the familiarity of face-to-face classroom for the uncharted terrain of the online environment.” This chapter was published in 2015, not 2021. However, we were already aware of the many challenges immigrants face and the difficulties of being undocumented in the U.S. in 2015. We were aware of ICE, and the violence immigrants face in North America. It feels cruel to compare an immigrant's experience, especially with the climate and hostility toward immigrants that existed in 2015 and still exists today, to teachers learning to teach online classes. From a rhetorical point of view, I'm not sure what Warnock hoped to accomplish through this misuse of language. The following is a written summary with key points included of the work referenced above and cited below. In Donald M. Murray's "Teach Writing as a Process Not Product," Murray implores us to abandon our traditional English training where we operate in a way that is entirely product-centered. As English scholars, many of us are trained in examining literature. However, what our students turn into us is not literature. They know it's not literature. We know that it is not literature. Yet, we assess it and possibly even deliver feedback on it where our critical attentions scan student writing as though it is literature. The final product of their writing doesn't impress us, we respond in kind, and they don't improve. Worse than that, we usually end up blaming the student and then we pass this student off to the next English teacher who possibly does the very same thing. If we teach composition with the realization that we are teaching a process, we may be able to break this cycle. We may create curriculums that work. We may encourage students rather than discourage them. Will this occur instantly once we have this revelation? No. After all, it is a process and processes to not conclude over night. Writing as a Process Teaching Composition, we can embrace teaching the process of discovery through language, the process of exploration, of using language to learn about the world, to evaluate what they've learned and eventually to communicate what they've learned through language. Murray remarks, "Instead of teaching finished writing, we should teach unfinished writing, and glory in its unfinishedness." I love this idea of glorying in unfinishedness, what Murray goes on to describe as, "language in action." There is elation in seeking out a word that fits what an idea you have in your head; we can teach students the journey of discovery and in so doing, impart some of the enthusiasm we have about English and rhet/comp. After all, most of us started our academic journeys because we felt great interest or great passion about our subjects. In teaching writing as a process, we move away from "good v bad," "incorrect v correct," "improper v proper." Instead, we empower students to make their own judgments and decisions. We create the space for inquiry and we welcome all of the consequences: probing questions, unique discoveries, and students finding their truths. Prewriting, Writing and Rewriting Murray breaks the writing process down into three stages: prewriting, writing, and rewriting. He describes prewriting as everything that occurs before the first draft is written. This is where the writer will encounter their subject. They will consider subject, secure their audience, and choose the way in which they want to communicate that subject to that audience. Writing, then, is the process of producing a first draft. The first draft is not a finished product, it is not literature; it is searching and unfinished. Finally, rewriting is rethinking all of the parts of the first draft including the subject, audience and form. Rewriting includes redesigning, reimagining, and reconsidering before rewriting and finally revising. How do you encourage writing as a process in the classroom? Murray would say that first, you have to shut up. If you're talking too much, your students aren't writing. If your students are writing, they're not practicing and therefore not discovering. Teaching writing as process requires great patience, lots of waiting, suspense, and ultimately, it requires that we respect our students. We respect our students not for the product they produce but for who their are in their journey to discovering their truth. If we respect students, we give them space and are willing to give them space to discover. We are also willing to listen, coach, encourage, and protect the learning environment so all of this may occur. There are implications of teaching process instead of product on the composition curriculum. Murray outlines ten such implications. Of these ten implications, this is what stood out to me:

Murray suggests that teachers reposition themselves in their teaching and view writing as process. To do this, it does not require a special schedule or bizarre resources. To teach writing as a process only requires a teachers willingness to do so, flexibility, and for a teacher to respect their students not for their finished work but for what they may do and who they may be is space is created for them to succeed and discover. Citations:

Donald Murray, "Teach Writing As Process, Not Product," in Rhetoric and Composition, ed., Richard L. Graves (Rochelle Park, New Jersey: Hayden Book Company, 1976), pp. 79-82. The following is a written summary with key points included of the work referenced above and cited below.

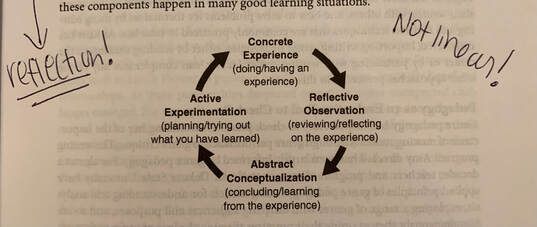

The introduction to Taggart, Hessler and Schick's text remembers their time as graduate students in Gary Tate's class considering a variety of approaches to composition pedagogy. 15 years later, they reflect that what they value most is a "combination of mentorship, focused reading, and critical self-reflection" (p. 1). There is no singular way to teach nor a unified set of goals every teacher should maintain exclusively. Instead, bringing self-awareness to our pedagogical choices as we are willing to blend and interact with varying approaches is a more illuminating path toward developing one's own composition pedagogy. Oftentimes, the field of rhetoric and composition circulates indirect, brief, or incomprehensive terms. Defining the word "Pedagogy" itself is equally difficult to pin down. In the 1st Edition of this book, they defined pedagogy as "the most commonly used, yet least defined, terms in composition studies.... the term variously refers to the practices of teaching, theories underlying those practices, and perhaps most often, as some combination of the two" (p. 2). Other scholars have defined pedagogy by building classification systems. Although there are a multitude of attempts to pin down a definition that is satisfying for composition pedagogies, one of the ones Taggart, Hessler and Schick found satisfactory was that of Nancy Myers: "Pedagogy suggests to me an ethical philosophy of teaching that accounts for the complex matrix of people, knowledge, and practice within the immediacy of each class period, each assignment, each conference, each grade... Historically, it accounts for the goals of the institution and to some extent society; it manifests the goals of the individual teacher, which may include an agenda to help students learn to critique both the institution and society; and it makes room for the goals of the individual students" (p. 3). Worth being considered, as Myers did, is the rhetorical situation of teaching itself -- people, the class, and the institution, etc. Thinking of writing pedagogy as a body of knowledge, Taggart, Hessler, and Schick offer up that composition pedagogy consists of "theories of and research on teaching, learning, literacy, writing, and rhetoric, and the related practices that emerge" (p. 3). At the intersection of theory, research, one's own teaching philosophy, and the rhetorical situation lies composition pedagogy. Good pedagogy is research-based. Taggart, Hessler, and Schick cite Chris Anson in a 2008 article where Anson resists a humanist tendency to depend solely on anecdotal evidence and instead to supplement experience with various kinds of data in order to challenge our own beliefs and also to support the case for good pedagogy (p. 5). Pedagogy is rhetorical (depending highly on the situation of each class) and personal (depending on the teacher's individual philosophies). So, what is the purpose of Pedagogy? Pedagogy influences the teaching and learning experience via meeting students needs, driving practices, generating practices, refining those practices, and examining all of the above. Good pedagogy is highly reflexive in nature. Because pedagogy functions in a multitude of ways, it can either push against or reinforce norms. To understand the role of pedagogies and their relationship to practice, Taggart, Hessler, and Schick bring in David Kolb's learning cycle. Pedagogy is not linear! Pedagogy responds to student's needs. In composition, we often have smaller classes that enable differentiated instruction according to individual needs. The student writers in our classrooms come from various backgrounds and a wide range of past experiences with writing. Pedagogies, often combined as needed, provide pathways to tailoring instruction according to student's needs.

Returning to an earlier idea of reinforcing or resisting norms, pedagogy can affirm the status-quo and adhere to traditional ideas (e.g. institutionalized grading of individuals), or disrupt normative socialization. If higher education reflects larger society, the same complex social issues and challenges that exist outside the institution exist inside the institution as well. Therefore, our pedagogies can create and mimic those challenges or revolutionarily resist them. In the text, A Guide to Composition Pedagogies, each pedagogy is separated out as a category. We should choose our pedagogies based on our own course goals and teaching philosophies while centering student's needs. We should also be willing to combine approaches and range widely. In summary, composition studies embraces pedagogy significantly more than other disciplines and there are many reasons for that. In the text, we will explore the various pedagogies and their importance while maintaining a student-centered classroom and reflexive practices. Citations: Tate, G., Rupiper, T. A., & Schick, K. (2001). A guide to composition pedagogies. New York: Oxford University Press. |

AuthorEmily M. Goldsmith (she/they) is a queer Cajun poet originally from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. They are currently a Ph.D. student at the University of Southern Mississippi. Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed