|

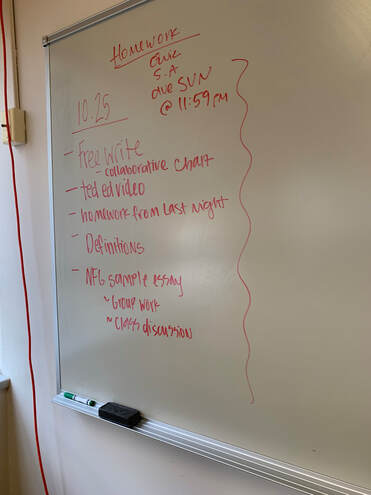

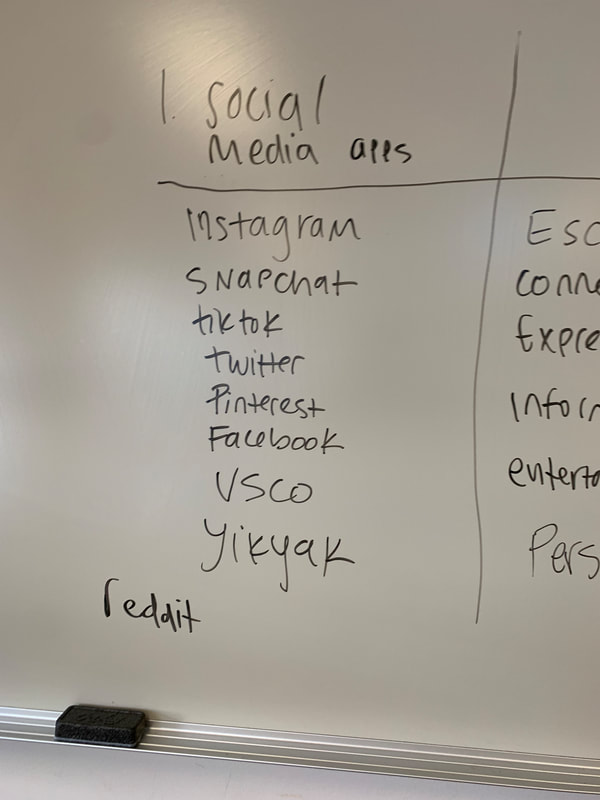

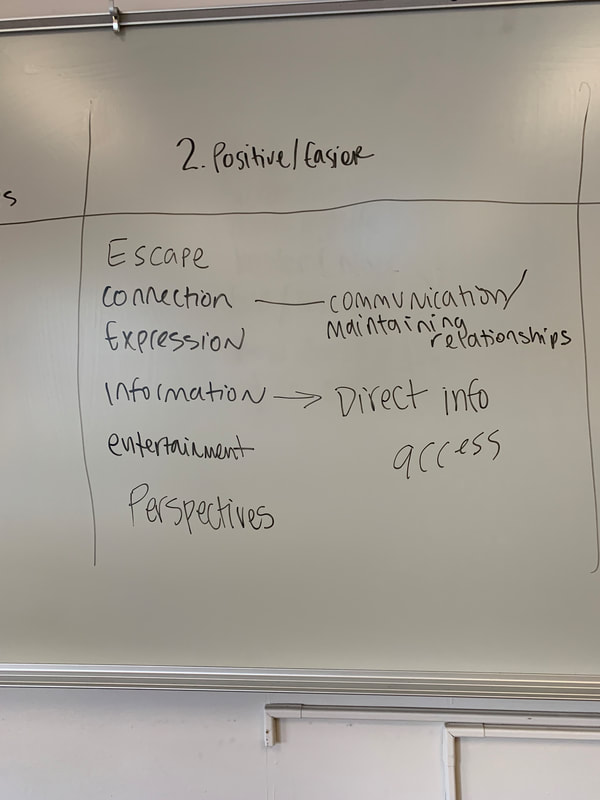

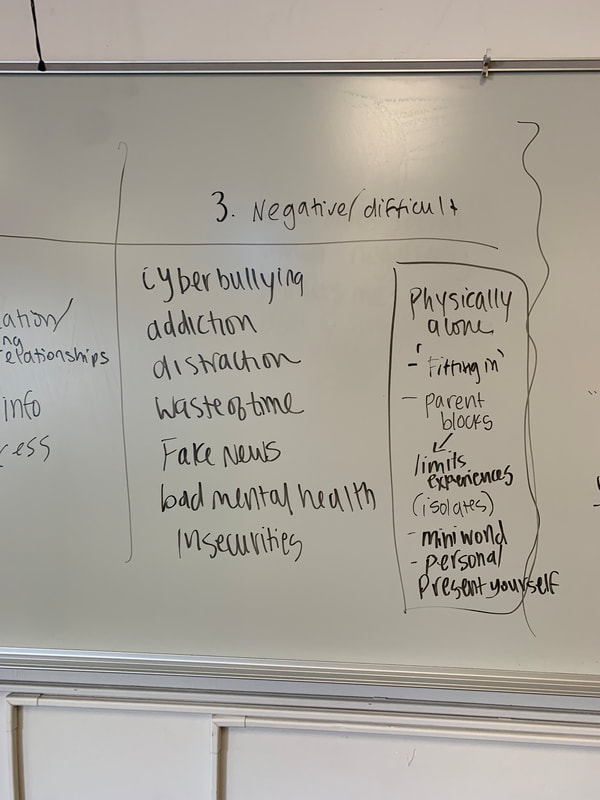

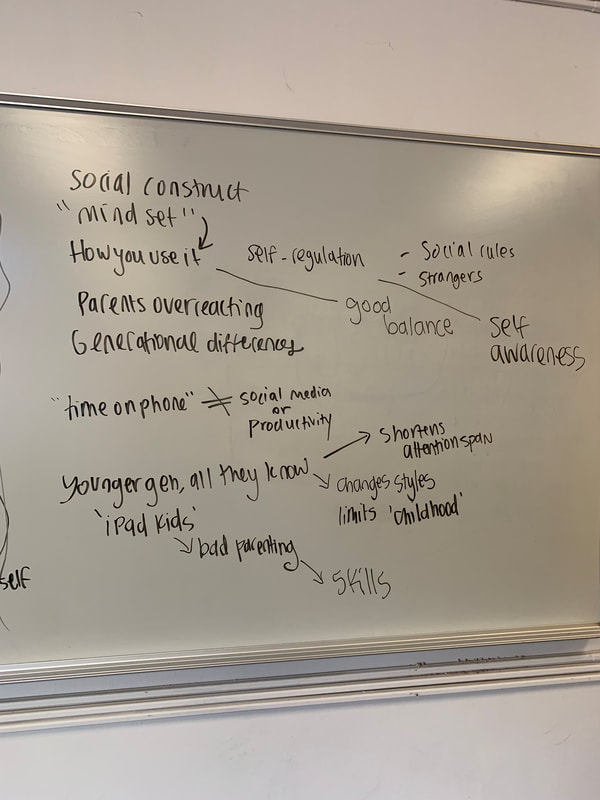

The last couple of weeks have been a unique challenge because students, especially first-year students, are facing more difficulty this semester than seemingly any semester prior. The ongoing pandemic may no longer be ushering us into virtual classrooms, but it continues to impact us in unforeseen ways. Students are exhausted, struggling, having a more challenging time focusing, and operating at lower energy levels than I’ve ever seen first-year students operate. I’m sure, years from now, someone will be able to label exactly what we’re experiencing, maybe they’ll even assign it a particular name or condition, but for those of us living it–we’re just making it day by day. I am remarkably proud of the work that these first-year composition students are producing, despite the challenges. We have made it through two out of three of our major units: visual analysis and textual analysis. We are in the midst of our final unit: a position paper; some would call this an ‘argumentative essay.’ We’ve been reading a variety of articles about social media, technology, and surveillance. These articles will eventually provide their sources for this upcoming major paper. We’ve had various discussions about the impact of social media on our lives: good and bad. We’ve hypothetically considered what life would be like without social media if it were to be banned. We’ve talked about app tracking and read about the quantity of time we spend on our phones and how that may be altering our brain chemistry. I’ve noticed that the most participation in one class session I’ve ever seen this semester was on the day we talked about social media. The semester is rapidly slipping away from us. It’s already the first week of November, and we have about one month left of Fall 2021, and Thanksgiving break is sandwiched in there. We’ll wrap up unit 3, they’ll turn in their third final paper, and we will work on revision in preparation for their final portfolio. I feel like the most important thing for me, at this point, is to continue caring about my students as people. I think that prioritizing empathy and kindness has to be first if we want to empower students to build lasting foundations in their academic journeys. With these additional difficulties, many of which are the result of COVID-19, I think this first year of college will determine whether students decide to continue on. I think of my role as helping them value critical thinking, believe they can succeed, learn time management skills, as well as demystify academia for them. If I can do that, the hope is that they have a strong enough foundation to push through, even when things feel hard—more complex than ‘normal.’ I fear we’ve lost what ‘normal’ was, and we may never get it back. It’s such a shame if that’s the case because I love teaching and learning, and I want students to enjoy learning. Suppose the university feels extraordinarily difficult with the pressures pushing in from external situations. In that case, we have to pivot inside the space we have—otherwise, we won’t be teaching well, and our students won’t be learning. I don’t have complicated solutions for doing this beyond ‘teaching against the grain,’ prioritizing empathy, eradicating busy work, thoughtfully building syllabi, purposefully assigning homework, and assessing in various ways. This week, I started reading Mike Rose’s Lives on the Boundary. I’m only a few chapters in but what I see through Rose’s autobiographical narrative and his reflections on our education system is that our systems have failed us. It isn’t that education isn’t a wonderful, powerful thing. It’s that the design of education is failing both students and teachers. We’re bending to the demands of neoliberalism, test scores, or nationalist ideologies rather than tailoring the educational system to the needs of learners. Much like the legacy of our nation and the manifest destiny imperial arm that casts a shadow over the America of possibilities, our education system is built to punish. It operates in a carceral fashion. Mike Rose thought of education as an invitation, and in so doing, he humanized his students in a way the system can’t. Instead of labeling students according to their failures, he saw a world that could be, and his compassion is evident in the lines of his 1989 book.  Works Cited Rose, Mike. Lives on the Boundary : a Moving Account of the Struggles and Achievements of America's Educationally Underprepared. New York, N.Y., U.S.A. :Penguin Books, 2005.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorEmily M. Goldsmith (she/they) is a queer Cajun poet originally from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. They are currently a Ph.D. student at the University of Southern Mississippi. Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed