|

The following is a written summary with key points included of the work referenced above and cited below. In Donald M. Murray's "Teach Writing as a Process Not Product," Murray implores us to abandon our traditional English training where we operate in a way that is entirely product-centered. As English scholars, many of us are trained in examining literature. However, what our students turn into us is not literature. They know it's not literature. We know that it is not literature. Yet, we assess it and possibly even deliver feedback on it where our critical attentions scan student writing as though it is literature. The final product of their writing doesn't impress us, we respond in kind, and they don't improve. Worse than that, we usually end up blaming the student and then we pass this student off to the next English teacher who possibly does the very same thing. If we teach composition with the realization that we are teaching a process, we may be able to break this cycle. We may create curriculums that work. We may encourage students rather than discourage them. Will this occur instantly once we have this revelation? No. After all, it is a process and processes to not conclude over night. Writing as a Process Teaching Composition, we can embrace teaching the process of discovery through language, the process of exploration, of using language to learn about the world, to evaluate what they've learned and eventually to communicate what they've learned through language. Murray remarks, "Instead of teaching finished writing, we should teach unfinished writing, and glory in its unfinishedness." I love this idea of glorying in unfinishedness, what Murray goes on to describe as, "language in action." There is elation in seeking out a word that fits what an idea you have in your head; we can teach students the journey of discovery and in so doing, impart some of the enthusiasm we have about English and rhet/comp. After all, most of us started our academic journeys because we felt great interest or great passion about our subjects. In teaching writing as a process, we move away from "good v bad," "incorrect v correct," "improper v proper." Instead, we empower students to make their own judgments and decisions. We create the space for inquiry and we welcome all of the consequences: probing questions, unique discoveries, and students finding their truths. Prewriting, Writing and Rewriting Murray breaks the writing process down into three stages: prewriting, writing, and rewriting. He describes prewriting as everything that occurs before the first draft is written. This is where the writer will encounter their subject. They will consider subject, secure their audience, and choose the way in which they want to communicate that subject to that audience. Writing, then, is the process of producing a first draft. The first draft is not a finished product, it is not literature; it is searching and unfinished. Finally, rewriting is rethinking all of the parts of the first draft including the subject, audience and form. Rewriting includes redesigning, reimagining, and reconsidering before rewriting and finally revising. How do you encourage writing as a process in the classroom? Murray would say that first, you have to shut up. If you're talking too much, your students aren't writing. If your students are writing, they're not practicing and therefore not discovering. Teaching writing as process requires great patience, lots of waiting, suspense, and ultimately, it requires that we respect our students. We respect our students not for the product they produce but for who their are in their journey to discovering their truth. If we respect students, we give them space and are willing to give them space to discover. We are also willing to listen, coach, encourage, and protect the learning environment so all of this may occur. There are implications of teaching process instead of product on the composition curriculum. Murray outlines ten such implications. Of these ten implications, this is what stood out to me:

Murray suggests that teachers reposition themselves in their teaching and view writing as process. To do this, it does not require a special schedule or bizarre resources. To teach writing as a process only requires a teachers willingness to do so, flexibility, and for a teacher to respect their students not for their finished work but for what they may do and who they may be is space is created for them to succeed and discover. Citations:

Donald Murray, "Teach Writing As Process, Not Product," in Rhetoric and Composition, ed., Richard L. Graves (Rochelle Park, New Jersey: Hayden Book Company, 1976), pp. 79-82.

0 Comments

The following is a written summary with key points included of the work referenced above and cited below.

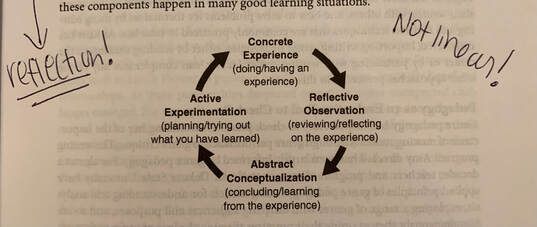

The introduction to Taggart, Hessler and Schick's text remembers their time as graduate students in Gary Tate's class considering a variety of approaches to composition pedagogy. 15 years later, they reflect that what they value most is a "combination of mentorship, focused reading, and critical self-reflection" (p. 1). There is no singular way to teach nor a unified set of goals every teacher should maintain exclusively. Instead, bringing self-awareness to our pedagogical choices as we are willing to blend and interact with varying approaches is a more illuminating path toward developing one's own composition pedagogy. Oftentimes, the field of rhetoric and composition circulates indirect, brief, or incomprehensive terms. Defining the word "Pedagogy" itself is equally difficult to pin down. In the 1st Edition of this book, they defined pedagogy as "the most commonly used, yet least defined, terms in composition studies.... the term variously refers to the practices of teaching, theories underlying those practices, and perhaps most often, as some combination of the two" (p. 2). Other scholars have defined pedagogy by building classification systems. Although there are a multitude of attempts to pin down a definition that is satisfying for composition pedagogies, one of the ones Taggart, Hessler and Schick found satisfactory was that of Nancy Myers: "Pedagogy suggests to me an ethical philosophy of teaching that accounts for the complex matrix of people, knowledge, and practice within the immediacy of each class period, each assignment, each conference, each grade... Historically, it accounts for the goals of the institution and to some extent society; it manifests the goals of the individual teacher, which may include an agenda to help students learn to critique both the institution and society; and it makes room for the goals of the individual students" (p. 3). Worth being considered, as Myers did, is the rhetorical situation of teaching itself -- people, the class, and the institution, etc. Thinking of writing pedagogy as a body of knowledge, Taggart, Hessler, and Schick offer up that composition pedagogy consists of "theories of and research on teaching, learning, literacy, writing, and rhetoric, and the related practices that emerge" (p. 3). At the intersection of theory, research, one's own teaching philosophy, and the rhetorical situation lies composition pedagogy. Good pedagogy is research-based. Taggart, Hessler, and Schick cite Chris Anson in a 2008 article where Anson resists a humanist tendency to depend solely on anecdotal evidence and instead to supplement experience with various kinds of data in order to challenge our own beliefs and also to support the case for good pedagogy (p. 5). Pedagogy is rhetorical (depending highly on the situation of each class) and personal (depending on the teacher's individual philosophies). So, what is the purpose of Pedagogy? Pedagogy influences the teaching and learning experience via meeting students needs, driving practices, generating practices, refining those practices, and examining all of the above. Good pedagogy is highly reflexive in nature. Because pedagogy functions in a multitude of ways, it can either push against or reinforce norms. To understand the role of pedagogies and their relationship to practice, Taggart, Hessler, and Schick bring in David Kolb's learning cycle. Pedagogy is not linear! Pedagogy responds to student's needs. In composition, we often have smaller classes that enable differentiated instruction according to individual needs. The student writers in our classrooms come from various backgrounds and a wide range of past experiences with writing. Pedagogies, often combined as needed, provide pathways to tailoring instruction according to student's needs.

Returning to an earlier idea of reinforcing or resisting norms, pedagogy can affirm the status-quo and adhere to traditional ideas (e.g. institutionalized grading of individuals), or disrupt normative socialization. If higher education reflects larger society, the same complex social issues and challenges that exist outside the institution exist inside the institution as well. Therefore, our pedagogies can create and mimic those challenges or revolutionarily resist them. In the text, A Guide to Composition Pedagogies, each pedagogy is separated out as a category. We should choose our pedagogies based on our own course goals and teaching philosophies while centering student's needs. We should also be willing to combine approaches and range widely. In summary, composition studies embraces pedagogy significantly more than other disciplines and there are many reasons for that. In the text, we will explore the various pedagogies and their importance while maintaining a student-centered classroom and reflexive practices. Citations: Tate, G., Rupiper, T. A., & Schick, K. (2001). A guide to composition pedagogies. New York: Oxford University Press. I'm processing week 1 of Fall 2021 as I write this reflection post. Being back on campus in person is a surreal experience. You can feel the vibrations of energy spread across the campus as students masked faces and wide eyes pepper the landscape. Even in the graduate classes I attend as a student, we are more talkative than normal. I don't need a second cup of coffee until the afternoon these days. My anxiety about COVID-19 exposure is met with equal parts joy to see folks excited about learning. What does that say about 'traditional' college-aged students and face-to-face instruction? It's saying something. Online classes are a fantastic accessible option that should certainly continue in appropriate volume per interest moving forward (beyond the pandemic) and we should all improve our online pedagogies. However, there is something special about a community of learners in a shared physical space. I don't think we can look past that either. What did I learn this week in theory? I listened to two podcast episodes from Pedagogue: Episode 30 and a bonus episode with advice for first-time teachers. Nancy Sommers, who gave advice for first time teachers, has taught composition and directed composition programs for thirty years. Sommers now teaches writing and mentors new writing teachers at Harvard's Graduate School of Education. Sommers initially began her comments focusing on building trust and building community on day 1 of class. In a rhet/comp class where we expect students to analyze texts, discuss their analysis, and peer critique work: trust is non-negotiable. How do we build community effectively? Sommers would remind us that we should remember our roots: we were called to the classroom and we are writers first. To be effective co-learners and learning facilitators, we have to consider our own values, be ourselves, and make the classroom our own. Jody Shipka, Associate Professor of English, is teaching courses in the Communication and Technology Track. Her research and teaching interests include multimodal discourse, digital rhetorics, play theory, materiality, and food studies. In Pedagogue Episode 30, Shipka discusses the idea of co-learning and being a student in your own classroom. Shipka remarked that they enjoyed teaching the most when they could learn from students and that students showed them what was possible. I appreciated the posturing of teachers not as experts of EVERYTHING but as experts of facilitation and preparing good prompting questions. How do we allow students to show us what is possible? How can we better shift away from the role of all-knowing expert to a true comrade in learning? What did I learn this week in practice? This week, I split up my 23 students into smaller groups (in response to COVID-19) and instructed the first 12 to attend class on Monday and the latter 11 to attend Wednesday. I organized them by alphabetical last names. On Monday, I facilitated an introduction with the first half of the class. Walking into the room a few minutes early, I set up the computer and projector. I logged into my email to download the PowerPoint I needed and opened the two websites I wanted to show them: Canvas and where to download the eBook. Then, I wrote my name on the board alongside the class number and description. I also wrote our objectives for the day in numerical order:

Another reason to tell students what is going to occur in the class is because, with adult learners, our students should be told what they’re doing and why they’re doing it! I opened the class session by playing music as students walked in the room. Promptly at 1:00pm, I greeted them and took roll. I quickly gave them a condensed course description. At this point, I introduced myself! The next activity functioned as an ice breaker: they introduced themselves one at a time and we went around the room hearing each students short intro. After that, I wrote “Community” on the board in all caps. I explained that in rhet/comp, we think about what words mean, how words are defined, and how to use language and syntax effectively for a position or argument or persuasion, etc. I asked them to call out what they thought about when they heard the word “Community.” The students offered up, “A group of people,” “a city,” “unity,” and “fellowship.” Together, we looked at the various definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary online. Then, we discussed how, when you belong to a community, you abide by unspoken and spoken rules. Transitioning into campus policies regarding COVID-19, we used the idea of belonging to a community where our decisions directly/indirectly impact others as a segue into discussing our university-wide policies regarding masks and self-reporting exposures. We went through a PowerPoint developed by Amy Carey, an instructor in English and director of the Writing Center at USM, regarding COVID-19. At this time, I paused for any questions or concerns. Considering communities and behaviors that are conducive to building community, I transitioned to our unique course policies (as outlined in the syllabus). These policies can be summarized as respecting one another, extending kindness in discussion, and setting up pathways to growth if incidents of offense occur. Our last activity was walking through the syllabus on the projector section-by-section. After we navigated the syllabus, we reviewed what the next two weeks of class would look like. Before I ended class for the day, I paused for any questions. The only questions I received were about COVID-19 and in-person learning versus online. Reflecting on Monday’s class, the 55-minute session was clear and well-paced. I left feeling like I had adequately prepared these students to understand the course and how to navigate it. Looking back, I felt like this group of students were “well-behaved” and extremely reserved. I wish I could’ve engaged them more in discussion and seen them loosen up. All students were first year freshman and most likely had only experienced high school classrooms that did not encourage laid back attitudes or discussion-based learning. We don’t change attitudes overnight, however, I walked away from this session asking myself – “How can I engage students more actively and involve them in active participation on Day 1?” I took this question about involving students immediately and encouraging participation into my Wednesday class with the remaining 11 students. I followed the same lesson plan as my Monday session but I did a few things differently. For one, I dressed less professionally according to the arbitrary interpretation of the word. Instead, I chose an outfit that was professional enough for the classroom but was more comfortable. As a result, I felt more like myself and I was more at ease - modeling that behavior to them. Secondly, I asked more questions and paused longer until someone answered these questions before continuing on. As a result, students were answering by the end of the class and a few stayed after to ask me general questions or just comment on the class. They seemed more relaxed in their posture during the class and they certainly participated more and asked more questions than Monday's class. When we defined "Community" together, they had great words to compose our definition: "church, school, workplace, sports team, acceptance, judgment, friendship, group of people, shared goal." I found that by asking follow-up questions, and pausing longer, I was able to engage more participants than Monday's attempt. Thinking about this week as a whole and my teaching practices: I am acknowledging the importance of asking follow-up questions, pausing for long stretches (even if it feels awkward), being okay with a little awkwardness in general, and being myself as a teacher because when I am at ease - students reflect that posture. Phrase I want to highlight from this post: "teachers as co-learners" Gloria Brown Wright (2011), author of Learner-Centered Teaching, makes the point that student's learning "should guide all decisions as to what is done and how." When the learner is centralized, the positions of student and teacher shift from their traditional placements, Maryellen Weimer (2002) states that the teacher changes from the "sage on the stage" to the "guide on the side." Teachers should shift away from thinking of teaching and learning as separate endeavors. As teachers model curiosity, learning that reflects creative and critical thinking, and learning as discovery, they illustrate learning as a lifelong practice. Citations: Wright, G. B. (2011). Student-Centered Learning in Higher Education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23(3), 92–97. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ938583.pdf Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Knowing that many of us teach students who have varying beliefs, diverse backgrounds, and unique opinions: encouraging all students to embrace campus-wide policies like wearing a mask can be a challenge.

Instead of politicizing the issue, I took my limited graphic design skills to Adobe Spark. As a funny/silly way of encouraging students to have positive attitudes about wearing their mask in the classroom and around campus, I created graphics like the one above using an image of a golden eagle (our campus mascot) wearing a mask! It feels strange at times to suspend our own attitudes or opinions in order to create space for each student. I feel as though a lot of us are navigating this terrain: how do we make space for every student to grow and learn without exposing marginalized students to additional harm or violence? I believe there is a way to do this. My personal solution would promote the ideas of building a classroom community from day 1, providing opportunities for student agency so they feel invested in the course, and outlining clear classroom policies with plans to engage in conversation if an incident occurs. Happy masking up to all! |

AuthorEmily M. Goldsmith (she/they) is a queer Cajun poet originally from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. They are currently a Ph.D. student at the University of Southern Mississippi. Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed