|

The following is a written summary with key points included of the work referenced above and cited below.

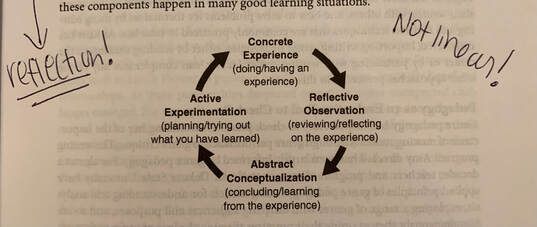

The introduction to Taggart, Hessler and Schick's text remembers their time as graduate students in Gary Tate's class considering a variety of approaches to composition pedagogy. 15 years later, they reflect that what they value most is a "combination of mentorship, focused reading, and critical self-reflection" (p. 1). There is no singular way to teach nor a unified set of goals every teacher should maintain exclusively. Instead, bringing self-awareness to our pedagogical choices as we are willing to blend and interact with varying approaches is a more illuminating path toward developing one's own composition pedagogy. Oftentimes, the field of rhetoric and composition circulates indirect, brief, or incomprehensive terms. Defining the word "Pedagogy" itself is equally difficult to pin down. In the 1st Edition of this book, they defined pedagogy as "the most commonly used, yet least defined, terms in composition studies.... the term variously refers to the practices of teaching, theories underlying those practices, and perhaps most often, as some combination of the two" (p. 2). Other scholars have defined pedagogy by building classification systems. Although there are a multitude of attempts to pin down a definition that is satisfying for composition pedagogies, one of the ones Taggart, Hessler and Schick found satisfactory was that of Nancy Myers: "Pedagogy suggests to me an ethical philosophy of teaching that accounts for the complex matrix of people, knowledge, and practice within the immediacy of each class period, each assignment, each conference, each grade... Historically, it accounts for the goals of the institution and to some extent society; it manifests the goals of the individual teacher, which may include an agenda to help students learn to critique both the institution and society; and it makes room for the goals of the individual students" (p. 3). Worth being considered, as Myers did, is the rhetorical situation of teaching itself -- people, the class, and the institution, etc. Thinking of writing pedagogy as a body of knowledge, Taggart, Hessler, and Schick offer up that composition pedagogy consists of "theories of and research on teaching, learning, literacy, writing, and rhetoric, and the related practices that emerge" (p. 3). At the intersection of theory, research, one's own teaching philosophy, and the rhetorical situation lies composition pedagogy. Good pedagogy is research-based. Taggart, Hessler, and Schick cite Chris Anson in a 2008 article where Anson resists a humanist tendency to depend solely on anecdotal evidence and instead to supplement experience with various kinds of data in order to challenge our own beliefs and also to support the case for good pedagogy (p. 5). Pedagogy is rhetorical (depending highly on the situation of each class) and personal (depending on the teacher's individual philosophies). So, what is the purpose of Pedagogy? Pedagogy influences the teaching and learning experience via meeting students needs, driving practices, generating practices, refining those practices, and examining all of the above. Good pedagogy is highly reflexive in nature. Because pedagogy functions in a multitude of ways, it can either push against or reinforce norms. To understand the role of pedagogies and their relationship to practice, Taggart, Hessler, and Schick bring in David Kolb's learning cycle. Pedagogy is not linear! Pedagogy responds to student's needs. In composition, we often have smaller classes that enable differentiated instruction according to individual needs. The student writers in our classrooms come from various backgrounds and a wide range of past experiences with writing. Pedagogies, often combined as needed, provide pathways to tailoring instruction according to student's needs.

Returning to an earlier idea of reinforcing or resisting norms, pedagogy can affirm the status-quo and adhere to traditional ideas (e.g. institutionalized grading of individuals), or disrupt normative socialization. If higher education reflects larger society, the same complex social issues and challenges that exist outside the institution exist inside the institution as well. Therefore, our pedagogies can create and mimic those challenges or revolutionarily resist them. In the text, A Guide to Composition Pedagogies, each pedagogy is separated out as a category. We should choose our pedagogies based on our own course goals and teaching philosophies while centering student's needs. We should also be willing to combine approaches and range widely. In summary, composition studies embraces pedagogy significantly more than other disciplines and there are many reasons for that. In the text, we will explore the various pedagogies and their importance while maintaining a student-centered classroom and reflexive practices. Citations: Tate, G., Rupiper, T. A., & Schick, K. (2001). A guide to composition pedagogies. New York: Oxford University Press.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorEmily M. Goldsmith (she/they) is a queer Cajun poet originally from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. They are currently a Ph.D. student at the University of Southern Mississippi. Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed